The worst railway line in London

If the District Line has a million haters I'm one of them. If it has one hater it's me. If it has 0 haters I have died.

If anyone reading this hasn’t had the experience of riding the District Line, I envy you.

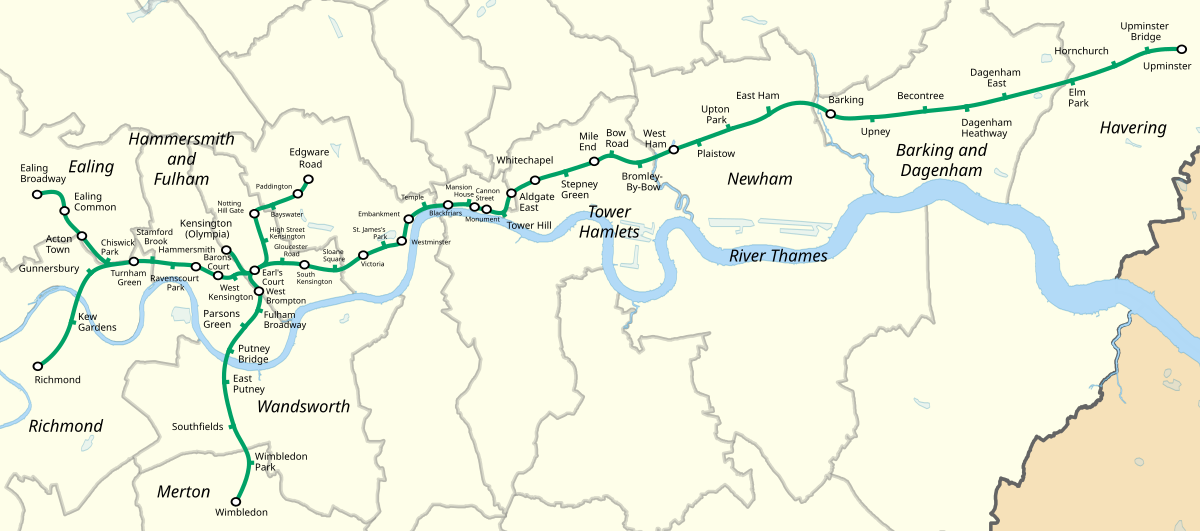

The District Line is one of London's many underground lines. The line runs across London from east to west and has a forked portion in the west (pictured below). The central point for the forking is Earl's Court, a station I've become intimately familiar with due to the amount of time I've spent waiting for trains that never arrive.

The line is the third oldest in London (behind the Hammersmith and Metropolitan lines), having opened in 1868. Consequently, it has a rather mixed history. The District Line started life as the Metropolitan District Railway, which began following the success of the Metropolitan Railway in 1863. The objective was to create an underground circle connecting London's railway termini.

There are a few methods to construct an underground railway. The two most common are cut and cover and Tunnel Boring Machines (TBM). Using cut and cover, you dig a trench, build the tunnel and then cover it back up. TBM’s in contrast are machines that will dig a tunnel underground, which has the advantage of not disrupting the surface and allowing you to dig a far deeper tunnel.

Whilst TBMs did exist at the time of the District’s construction, the method chosen to build the line was 'cut and cover'. This was because of the use of steam trains, which required frequent openings to allow steam to escape. As a result, the District Line is only about 5 metres underground - typical deep-level Tube lines are 24 metres deep.

By the start of the 20th Century, the underground railways had become a convoluted system of operators with multiple similar lines overlapping. In 1933, all of London's underground lines were brought together under the London Passenger Transport Board - the District Railway was now known as the 'District Line', and parts of its branches were transferred to other lines.

After the war, the District Line was nationalised, but at the turn of the millennium, it was partly privatised in a public-private partnership; it is now back to being run solely by TfL.

Before I start complaining, I must acknowledge that the London Underground is the oldest transport system in the world and has some of the highest ridership globally. It was the cutting-edge system at the time, and there are countless efforts to bring it into the modern age.

But I hate the District Line.

The District Line is slow, with a listed max speed of 100 km/h, but its average speed is a paltry 29 km/h. On top of this, it has the most stations of any Tube line, which means you're constantly stopping. This is further exacerbated by the fact that the District Line is constantly delayed. As a result, using the District Line is a frustrating experience. But that's only the beginning.

The timetable is quite literally never accurate for the District Line. I have repeatedly been waiting for a train to turn up, only for it to never appear, as if it has become a ghost train.

To further rub in the pain, District Line trains often seem indecisive about where they want to go.

Whenever you have the displeasure of getting on the District line from the Wimbledon branch, you can bet your entire life savings that the train will change destination at Earl's Court, sometimes multiple times.

One fateful morning, after staying at a friend's house which is unfortunately on that branch, I woke up early to get the train to work, knowing the issues with the District Line.

8:20 am: I arrive at the platform - perfect, the train is meant to arrive in 5 minutes.

8:30 am: No train in sight. The platform is now packed.

8:35 am: The train arrives, it's heaving, but I need to get on.

Phew, it's a train going the right way; it's a 26-minute journey, I'm good. Then, as the train approaches Earl's Court, you see the crowd on the platform all waiting to board your already packed train.

Thankfully, you're already on the train. But then suddenly, the dreaded tannoy announces, "This train is now for Ealing Broadway" - now the wrong way.

At this point, there's a stampede, not much unlike that of elephants on the Serengeti, of people leaving the train. As you manage to get some breathing space on the platform, you turn around to see this barren train suddenly revert to its original direction. But by then, you're too far away, and the crowd, like the tide, flows back onto the train. The next train is in 10 minutes.

You are now late.

The list of problems I have with the District Line is endless.

Why, on a train line that is barely underground, am I in the 21st century unable to get data? Yet on the Jubilee Line, which is nearly six times as deep, I can get 5G.

Why does a line with clearly enormous demand run such a small number of trains? Waits of 15 minutes for a Wimbledon train are not uncommon, especially if the train you are waiting for decides to become the Flying Dutchman, never blessing the station you're waiting at.

The reasons for this are largely due to signalling. As previously mentioned, the District Line is one of the oldest lines on the Underground, and its signalling systems are some of the oldest.

A brief lesson in train signalling: conventional train signalling is also called Fixed Block Signalling. Essentially, drivers manually drive the train using trackside signals to determine if they can go forward and at what speed. This is done by a traffic light system, one which you can often see at the track.

At the signalling side, the track is divided into what are called fixed blocks - a block is about 300 metres of track - in which trains operate. This is because traditional signalling systems don't actually know where a train is exactly; they know only which block a train is in. Therefore, the signalling operator will mark the current block and the block in front as unavailable for safety. The signalling lights are used to tell drivers when they can progress through each block. To prevent a train from going past a signal, they have what are known as 'tripcocks' - mechanical devices that will stop a train if it progresses past a red signal.

In contrast, the modern version of signalling is called Communications-based Train Control (CBTC). This is a system where the trains and track equipment communicate, allowing the system to know exactly where each train is, down to the centimetre. The system is also centrally controlled versus traditional signaling which requires many railway signallers along the line. This provides a significant advantage in increasing train frequency, as you no longer need to allocate additional block space for safety, as well as allowing the line to be controlled from one operations room.

The other advantage of CBTC is that you can use Automatic Train Operation (ATO), which allows the trains to operate automatically, no longer requiring the driver to start and stop the train. This is a significant improvement over traditional signalling as it allows trains to maximise their throughput and increase speed. Meaning you can increase capacity on the exact same set of tracks.

CBTC has been rolled out to some parts of the District Line via a programme called the Four Lines Modernisation, which has led to significant improvements on some sections of the line. However, as with essentially every infrastructure programme in the UK, there have been significant delays. As a result, large chunks of the District Line in the west haven't been modernised and are currently deferred indefinitely.

This means each train goes through a patchwork of signalling systems, and drivers are required to use both an automatic and a manual driving system on each journey. Which essentially negates the advantage of using CBTC. In theory, my issues for the District line should be resolved once they have fully upgraded to CBTC.

However, knowing how long infrastructure projects take in the UK, I could be waiting a while.