A 24 year old's thoughts on careers

The classic dilemma of a young adult

Often touted by life gurus is the idea of simplifying your life. Think about the number of decisions you have to make on a daily basis: what to eat, whether to work out, what to wear. Your life is one of constant decisions from the moment you wake up till the moment you fall asleep - on average 35,000 a day.

The consequence of this is often decision fatigue. Decision fatigue is a rather fascinating concept, one commonly exploited by supermarkets. After shopping around in a stressful supermarket after a long day, you are significantly more likely to pick up chocolate or a sweet treat if it is right there at the till. That is because your quality of decisions has significantly decreased after having to make so many previously.

The usual suggestion to avoid decision fatigue is to wear the same outfit. The classic example of this being Steve Jobs – below wearing his iconic outfit.

However, whilst this might be helpful in smaller decisions, what is often less discussed is helping make the decisions that often have the most influence over your life. This is typically two things; who you will marry and what you will do as a career.

The decision point about career seems to hit every person in their early 20s. A point at which you move from being an emerging adult to a young adult. And often this gives most young people the feeling that their life is over by the age of 25, even if their life has only just begun.

The crux of the problem at 25 is you have largely led a life with decisions made by other people for you. You have lived life with guardrails. However, at this point, your career is now your own, and there are far too many choices to make. You have so many choices but can't narrow them down and often delay making a choice.

The starting point that my boss shared with me, and would share with anyone, is that you have to make a determination of where you want to be. This is both country and city; location matters far more than the specific job. From there, making the choice around your career becomes easier.

I remember talking to a friend about this – I, as I will probably write about in the future, am a big NBA fan (I am currently winning my fantasy league to flex my analytical knowledge on clueless Americans). And I said to him, on one of the many 4 a.m. chats that I am known for, that I envy professional athletes, not because of the money but because of the simplicity. If you are an NBA player, your entire life – for an average 5-year career – is focused around getting better at basketball.

This is no mean feat, obviously, and comes with challenges around what you focus on. But at the end of the day, you know you must focus on winning the game when it counts.

This simplicity in objectives is a feature of a couple of different careers, most notably Medicine. The path for Medicine in the US and the UK is roughly the same: you go to university, then med school (skipped in the UK), then additional training to specialise, then potentially further specialisation, at which point you are a fully qualified doctor in your field.

Obviously, each of those steps is fraught with difficulty and choice. You end up committing 15 years of your life to pursuing that goal. But at the end of the day, you are becoming a doctor on a largely guard-railed career path.

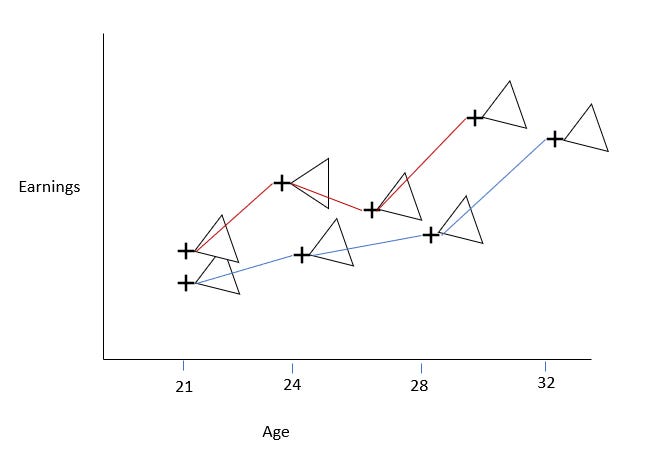

Yet, for the rest of us, a "career" is a rather nebulous thing, defined by many twists and turns. When presenting my concerns to my boss – who is a key proponent of taking the slow path in life, and often stresses that young adults now have a burning desire for progression that he doesn't understand – he shared a rather good chart that I have re-drawn below.

The point the chart is trying to illustrate is that for every single person, the path is different. And with each move you make in your career, there is always a range of potential with each role. Some of them may pan out, some may not. But the objective of each move is to ensure you have forward momentum. That is key; always have momentum and just get started are probably the biggest lessons I have learnt from him. But also, key is the fact that someone may jump ahead of you, but you can always catch up. The Y-axis in this case was earnings, but it doesn't always have to be; it could be prestige, work-life balance, etc., whatever you value.

When viewed from that angle, the idea of a career is a significantly less daunting concept. The next role is not the end of the world; your life is not over at 25, 35, or 50. You can perpetually fail for 20 years but still end up with a great life, as long as you optimise for whatever you want.

A lesson that is hard to internalise but rather self-obvious when reflected upon, and I hope helpful for anyone in their 20’s having the same dilemma.