Why can't I find Frozen Blueberries

A short analysis on the supply chain of Blueberries

For six month now I couldn’t find a frozen blueberry. No matter what day of the week, whether its Monday, Wednesday, or Sunday. Nor whatever time it is 8am, 2pm or 10pm.

My final stop in the store is always the long walk down the freezer aisle culminating in a bare shelf with a sad out of stock sign. This has become the frustrating end of my visits to the supermarket.

Now of course, any normal person would simply move on with their day and pick up a bag of raspberries (which are interestingly also going through a shortage) or blackberries - disregarding the fact that oftentimes there simply isn’t a berry to be spied. But for me, I quickly fell down the rabbit hole of trying to understand the supply chain of blueberries.

Food security and supply chains are incredibly important and underpin essentially everything in our lives. However, they are largely a solved issue in the Western World. This is due to their unrivalled complexity that is running all around us, but goes completely unnoticed almost every day.

The humble blueberry is a true example of the scale and complexity of these supply chains.

Global production of blueberries as of 2021 is 1.1 million tons. A large chunk of this comes from the United States, Peru, and Canada making up 65% of global production collectively. This is how blueberries are - largely - available all year round with opposite growing seasons. The global blueberry market is expected to reach $13.4 billion by 2027.

In the UK only a tenth of our blueberries are grown here, and of course during Winter we have to import from Peru or Chile.

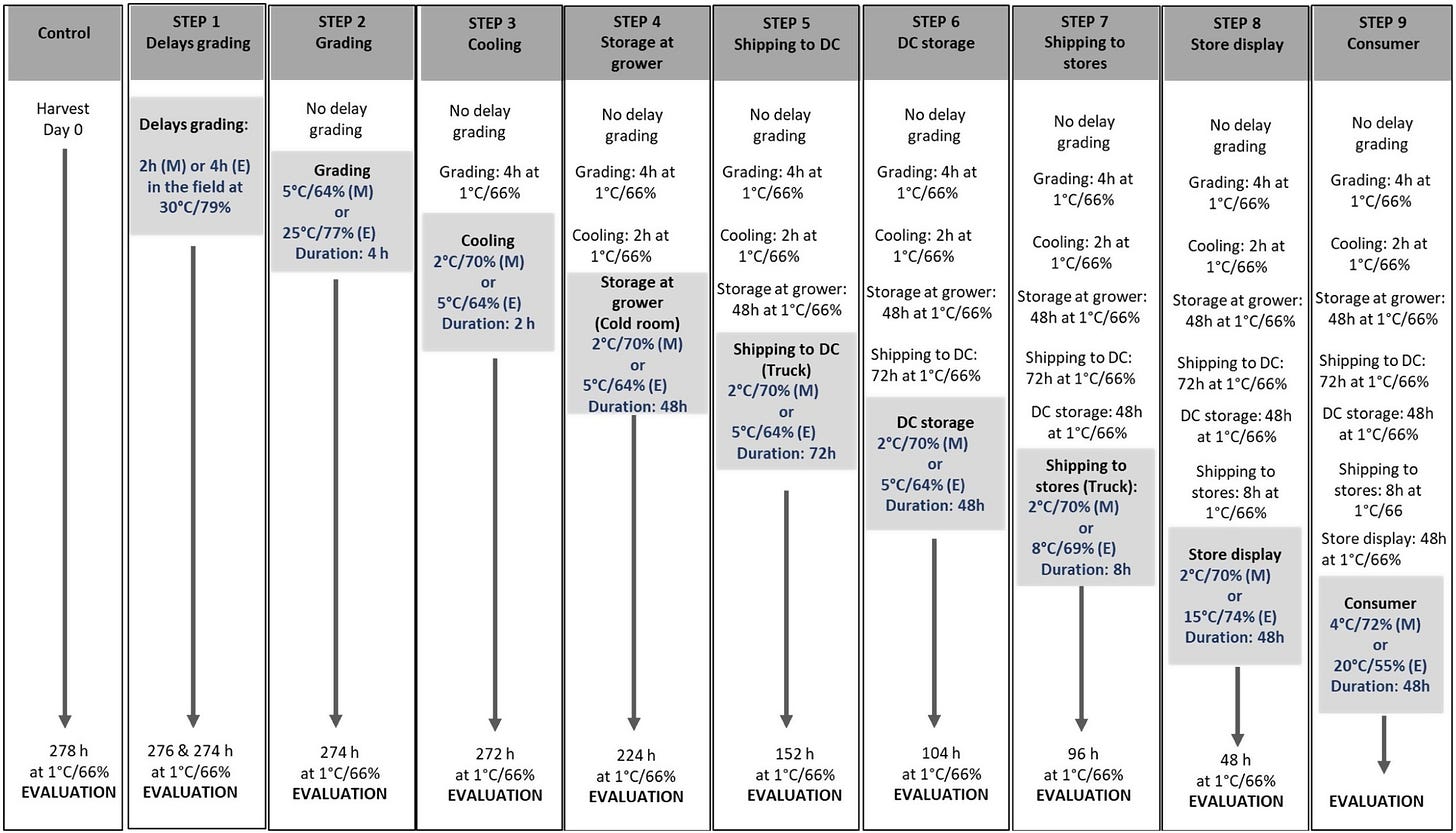

This is rather typical of all fruit, but 95% of the worlds blueberries are transported by ship. The shelf-life for fresh blueberries can range from 1-8 weeks depending on pre-harvest conditions and how they are transported. Something that you would struggle to believe as they seemingly go off in a matter of days in your kitchen. Below is a rather nerdy chart, that I was delighted to find, showing the supply chain for blueberries over 11 days.

Once they are picked the blueberries that are destined for my smoothie are subjected to the ‘quick-freezing process’. The process brings blueberries down to -18°C (-0.4F). After that they are now stable and can be stored or shipped. However, for fresh blueberries the story is a little more complex.

Blueberries unlike some fruit do not improve after harvest, therefore they are picked at their fully ripe stage and so begins a race against the clock. Due to such long distances between picking and consumption the average loss in the process is around 10%. This has caused significant interest in the improvement of the logistics in transporting blueberries.

The two major methods in the supply chain to improving shelf life of fresh blueberries - and technically anything - are the use of Controlled Atmosphere (CA) and Modified Atmosphere Packing (MAP).

Essentially CA is ensuring the correct balance of Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide in the cold storage units, they will engineer the levels of Carbon Dioxide and Oxygen to be around 10% and 11% respectively whilst being stored and shipped - This can extend the market supply of blueberries to 8 weeks. However, CA can cause undesirable effects in blueberries such as changes in taste and firmness. Especially if the Carbon Dioxide levels climb above 12%.

Whereas MAP is far more interesting - What they will do is wrap the boxes of blueberries in packaging like below - often in polyethylene - then remove the air and reintroduce the desired atmosphere. This is typically 2-5% Oxygen, 20% Carbon Dioxide and the remaining gas being Nitrogen.

Modified Atmosphere Packing has been in use regularly since the 1970s in fish and meat. With each product having different optimal gas mixtures. Red meat for example is often packed with 85% Oxygen and 15% Carbon Dioxide.

This has the effect of reducing weight loss due to increased humidity within the packaging and has the same shelf life extension as CA, without any of the undesirable side effects.

All in all these innovations - which have been used in blueberry logistics since roughly 2011 - have tripled the overall supply period from 21 days to 60 days. It has helped reduce the weight loss of blueberries in transport by more than half, has helped retain more of the nutritional values in blueberries, and has improved the quality of blueberries at the consumer level.

Now whilst all very interesting, the real reason I ended up deep diving into logistics was simply because I want frozen blueberries for my morning smoothie.

The actual reason I seem incapable of finding them is much simpler, the El Niño phenomenon which recently occurred in 2023/24 resulted in a 23% decrease in Peru’s blueberry export volume, which combined with a massive growth in demand for blueberries worldwide has obviously led to shortages and increased prices.

This combined with declining imports of frozen berries to the UK, has culminated in me frequently staring at an empty shelf whilst damming the CEO of Morrisons. Something my friends are keen to point out they do not experience in their own supermarket.

Although good news for the blueberry fans amongst us, more stable weather conditions and increased planting in the 2024/25 season is set to give significant supply boosts to Peru’s bloobs. So hopefully - very soon ideally - I will be able to have my blueberry smoothie once again.