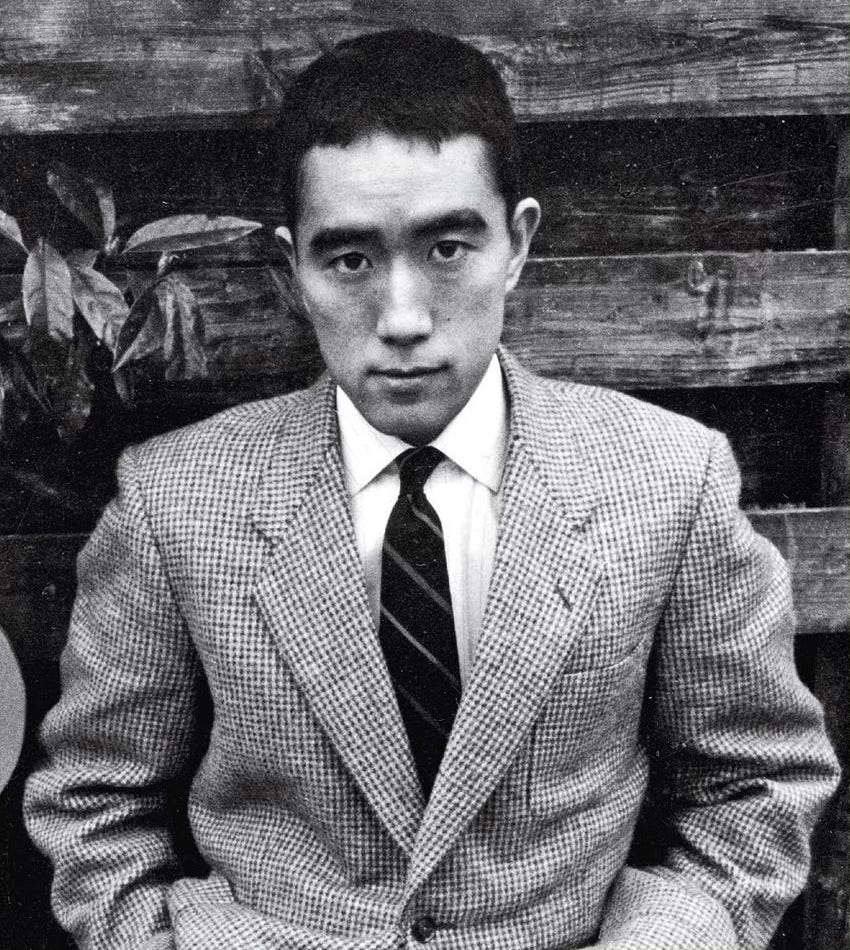

Yukio Mishima

A controversial figure

The concept of beauty, death, and seppuku runs deeply throughout Yukio Mishima’s life.

Born in 1925, Mishima lived through imperial Japans peak and its dramatic collapse. At its height in 1942, Japan controlled — in part or in whole — some twenty different countries, held a quarter of China, and governed a third of its population. It was the pre-eminent power in Asia, rivalling the Nazis in strength. Yet by 1945 it collapsed as quickly as it had risen.

Napoleon is quoted as saying, “To understand the man you have to know what was happening in the world when he was twenty.”

Mishima was always an ill child; early in life he was stolen away by his grandmother so she could look after him.

Not allowed to leave the house, living as a recluse and becoming pale and sickly. It was there that his love for books began.

Once returned to his family at age twelve, Mishima had already started writing. His father, however, did not take kindly to it and tried to stifle his passion by destroying his work, among other things. Mishima resisted, writing in secret.

During the war, Mishima desperately wanted to be a soldier and fight for Japan. However, he never left home as he had contracted tuberculosis and was exempted. Mishima suffered survivors guilt from never serving in the war.

Mishima took pride in that he was directly descended from Tokugawa Ieyasu — the famous shogun (military dictator) of the sixteenth century — through his grandmother.

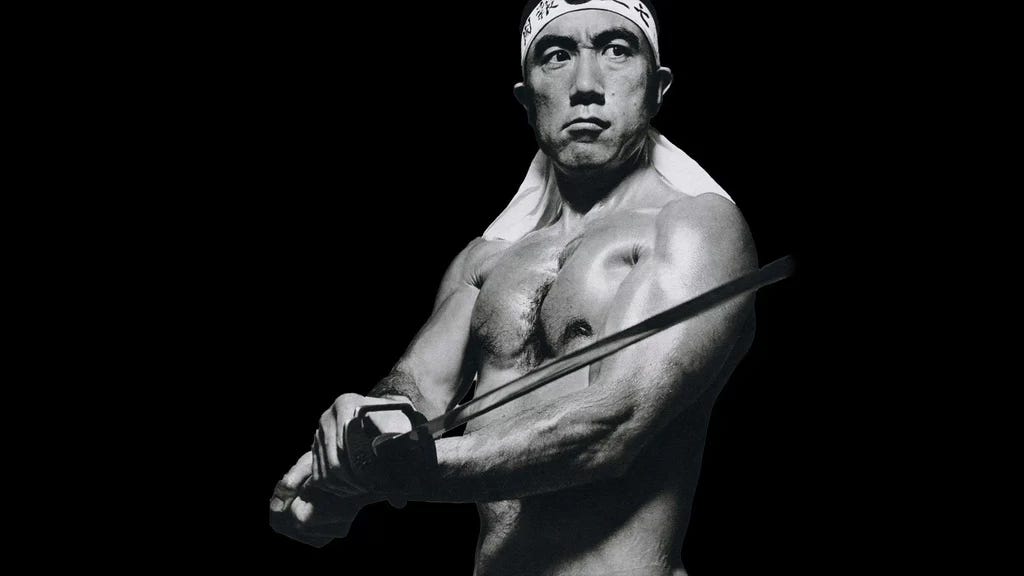

Despite his sickly childhood, Mishima became fascinated with Ancient Greece and the physiques of its warriors. This both tormented and fuelled his desire for perfection. Tied in with this was an infatuation with death and the sensuality and beauty he believed it inherently possessed.

‘We live in an age in which there is no heroic death.’ — Yukio Mishima

To Mishima, the death of modern man in a hospital bed is a travesty.

In his words: “Modern man can no longer die a dramatic death. Instead, he dies in a hospital room, like a bee inside a honeycomb cell. Death in the modern age, whether due to illness or accident, is devoid of drama.”

Alongside this unique view of death are what could be plainly called nationalist or far-right views. Mishima was devoted to the idea of Japan prior to the Second World War.

Mishima’s nationalism developed due to the decline of Japanese culture; he felt as though the Japanese had abandoned their history and turned away from tradition in favour of consumerism.

Mishima viewed himself as out of place in the world — a man of action, a samurai, compelled by bushido. He called himself “the last of my kind” for this reason. That nostalgia permeates his work.

Yet what is odd about Mishima is that he was a modern writer. He was a celebrity during his prime, an actor, and a public intellectual. His work is so deeply rooted in tradition, yet he embraced the form of cinema and wove modernity together with tradition in his writing.

Immensely prolific, he produced hundreds of works in almost every genre. His novels Confessions of a Mask (1948) and The Temple of the Golden Pavilion (1956) were among the first works of modern Japanese fiction to win an international readership. Mishima was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature five times for his novels, poems, and plays.

Mishima’s work covers a wide range of topics, from the existential angst of human existence to societal norms and pressures. He explored taboo concepts such as sexuality, death, brutality, and violence.

His tendency to challenge these norms and concepts in his works pushed the boundaries of literature and led to his works being remarked upon in Japanese society.

Yet the end of his life was as spectacular as the prose of his stories.

On the afternoon of the 25th of November 1970, Mishima and four of his men took the base commander of a Self-Defence Force base hostage. After issuing a demand that all personnel at the base assemble in front of the main building, Mishima spoke to them from the balcony for several minutes inspiring them to overthrow the Government.

He then committed seppuku.

After his death, Mishima became arguably more controversial. There are few other writers so defined by their final action.

His motives are still up for debate. Was Mishima really being patriotic, or were his actions ultimately a narcissistic effort to satisfy himself?

Mishima never quite got over not dying in the war. He felt survivor’s guilt and confessed that he had an “inferiority complex” about not having had the courage to volunteer for the battlefield. A dislike of growing old permeates his work; he never envisioned living past fifty.

Despite this, Mishima is a literary genius. His works are regarded as some of the greatest pieces in Japanese literature. They captivate readers with interest, confusion, psychological depth, and provoking themes. His prose spectacularly weaves all these elements together in a way that leaves you wanting more.

Yukio Mishima’s legacy can be categorised in different ways: a visionary artist, a nationalist, a controversial figure, and a rebel. His works often remind us that sometimes it is difficult for things to be objective, and his persona reflected the human mind.